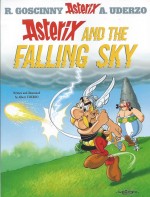

By Uderzo, translated by Anthea Bell & Derek Hockridge (Orion Books)

ISBN: 978-0-7528-7548-4

Asterix began life in the last year of the 1950s and is part of the fabric of French life. His adventures have touched billions of people all around the world over the decades. However when this particular tale was released it was like nothing anybody had ever seen before. It fact it is considered to be the most controversial and least well-regarded by purists. Some even hate it…

They are all welcome to their opinions. I must admit that I too found it a little unsettling when I first read it. So I read it some more and saw the elements that I’d initially had trouble with weren’t lax or lazy or bad but just not what I was expecting. Soon it became one of my favourites just because it was so different.

Uderzo was and is a comics creator par excellence. With Rene Goscinny he created, owned and controlled his intellectual property Asterix and used it to tell the tales he wanted to tell.

It was his right to say and draw whatever he wanted to through his creation and nobody has the right to dictate what he could or could not do with it as long as no laws were broken.

It’s a lesson the whole world needs to learn, now more than ever…

A son of Italian immigrants, Alberto Aleandro Uderzo was born on April 25th 1927 in Fismes on the Marne. He dreamed of becoming an aircraft mechanic but even as a young child watching Walt Disney cartons and reading Mickey Mouse in Le Pétit Parisien he showed artistic flair.

Albert became a French citizen when he was seven and found employment at thirteen, apprenticed to the Paris Publishing Society, where he learned design, typography, calligraphy and photo retouching. He was brought to that pivotal point by his older brother Bruno (to whom this volume is gratefully and lovingly dedicated for starting the ball rolling) but when World War II reached France he moved to Brittany, spending time with farming relatives and joining his father’s furniture-making business.

The region beguiled and fascinated Uderzo and when a location for Asterix‘s idyllic village was being mooted, that beautiful countryside was the only possible choice…

In the post-war rebuilding of France, Uderzo returned to Paris and became a successful artist in the recovering nation’s burgeoning comics industry. His first published work, a pastiche of Aesop’s Fables, appeared in Junior and in 1945 he was introduced to industry giant Edmond-François Calvo (whose own comic masterpiece The Beast is Dead is far too long overdue for a commemorative reissue…).

Tireless Uderzo’s subsequent creations included the indomitable eccentric Clopinard, Belloy, l’Invulnérable, Prince Rollin and Arys Buck. He illustrated Em-Ré-Vil’s novel Flamberge, dabbled in animation, worked as a journalist and illustrator for France Dimanche and created the vertical comicstrip ‘Le Crime ne Paie pas’ for France-Soir.

In 1950 he illustrated a few episodes of the franchised European version of Fawcett’s Captain Marvel Jr. for Bravo!

An inveterate traveller, the artistic prodigy first met Goscinny in 1951. Soon bosom buddies, they resolved to work together at the new Paris office of Belgian Publishing giant World Press. Their first collaboration was published in November of that year; a feature piece on savoir vivre (gracious living) for women’s weekly Bonnes Soirée, following which an avalanche of splendid strips and serials poured forth.

Jehan Pistolet and Luc Junior were created for La Libre Junior and they resulted in a western starring a “Red Indian†who eventually evolved into the delightfully infamous Oumpah-Pah. In 1955, with the formation of Édifrance/Édipresse, Uderzo drew Bill Blanchart (also for La Libre Junior), replaced Christian Godard on Benjamin et Benjamine and in 1957 added Charlier’s Clairette to his portfolio.

The following year, he made his debut in Tintin, as Oumpah-Pah finally found a home and a rapturous audience. Uderzo also drew Poussin et Poussif, La Famille Moutonet and La Famille Cokalane.

When Pilote launched in 1959 Uderzo was a major creative force for the new enterprise, collaborating with Charlier on Tanguy et Laverdure and devising – with Goscinny – a little something called Asterix…

Although the gallant Gaul was a monumental hit from the start, Uderzo continued on Les Aventures de Tanguy et Laverdure, but once the first hilarious historical romp was collected in an album as Ast̩rix le gaulois in 1961 it became clear that the series would demand most of his time Рespecially since the incredible Goscinny never seemed to require rest or run out of ideas.

By 1967 Asterix occupied all Uderzo’s time and attention, and in 1974 the partners formed Idéfix Studios to fully exploit their inimitable creation. When Goscinny passed away three years later, Uderzo had to be convinced to continue the adventures as both writer and artist, producing a further ten volumes until 2010 when he gracefully retired.

After nearly 15 years as a weekly comic serial subsequently collected into book-length compilations, in 1974 the 21st (Asterix and Caesar’s Gift) was the first published as a complete original album prior to serialisation. Thereafter each new release was an eagerly anticipated, impatiently awaited treat for the strip’s millions of fans…

More than 325 million copies of 35 Asterix books have sold worldwide, making his joint creators France’s best-selling international authors, and now that torch has been passed and new sagas of the incomparable icon and his bellicose brethren are being created by Jean-Yves Ferri and Didier Conrad…

One of the most popular comics on Earth, the collected chronicles of Asterix the Gaul have been translated into more than 100 languages since his debut, with numerous animated and live-action movies, TV series, games, toys, merchandise and even a theme park outside Paris (Parc Astérix, naturellement)…

Like all the best stories the narrative premise works on more than one level: read it as an action-packed comedic romp of sneaky and bullying baddies coming a-cropper if you want, or as a punfully sly and witty satire for older, wiser heads. English-speakers are further blessed by the brilliantly light touch of master translators Anthea Bell & Derek Hockridge who played no small part in making the indomitable little Gaul so very palatable to English tongues.

Many of the intoxicating epics are set in various exotic locales throughout the Ancient World, with the Garrulous Gallic Gentlemen reduced to quizzical tourists and bemused commentators in every fantastic land and corner of the civilisations that proliferated in that fabled era. The rest – more than half of the canon – take place in and around Uderzo’s adored Brittany, where, circa 50 B.C., a little hamlet of cantankerous, proudly defiant warriors and their families resisted every effort of the mighty Roman Empire to complete the conquest of Gaul.

The land is divided by the notional conquerors into provinces of Celtica, Aquitania and Amorica, but the very tip of the last named just refuses to be pacified…

Whenever the heroes were playing at home, the Romans, unable to defeat the last bastion of Gallic insouciance, futilely resorted to a policy of absolute containment. Thus the little seaside hamlet was permanently hemmed in by the heavily fortified garrisons of Totorum, Aquarium, Laudanum and Compendium.

The Gauls couldn’t care less, daily defying and frustrating the world’s greatest military machine simply by going about their everyday affairs, protected by the miraculous magic potion of resident druid Getafix and the shrewd wits of the diminutive dynamo and his simplistic, supercharged best friend Obelix…

This particular iconoclasm, Uderzo’s eighth solo outing (and originally entitled Le Ciel lui tombe sur la tête) was released in 2005 as the 31st volume of an ever-unfolding saga. The English language version was released that same year as Asterix and the Falling Sky. Apart from the unlikely thematic content and quicker pacing, the critics’ main problem seemed to stem from a sleeker, slicker, less busy style of illustration – almost a classical animation look – but that’s actually the point of the tale.

The entire book is a self-admitted tribute to the Walt Disney cartoons of the artist’s formative years, as well as a sneakily good-natured critique of modern comics as then currently typified by American superheroes and Japanese manga…

The contentious tale opens with the doughty little Gaul and his affable pal Obelix in the midst of a relaxing boar hunt when they notice that their quarry has frozen into petrified solidity.

Perplexed, they head back through the eerily silent forest to the village, only to discover that all their friends have been similarly stupefied and rendered rigidly inert…

Only faithful canine companion Dogmatix and the old Druid Getafix have any life in them, but only when Obelix admits to giving the pooch the occasional tipple of Magic Potion does Asterix deduce that it’s because they all have the potent brew currently flowing though their systems…

With one mystery solved they debate how to cure everybody else – as well as all the woodland creatures and especially the wild boars – but are soon distracted by the arrival of an immense golden sphere floating above and eclipsing the village…

Out of if floats a strange but friendly creature who introduces himself as “Toon†from the distant star Tadsilweny (it’s an anagram, but don’t expect any help from me). He is accompanied by a mightily powered being in a tight-fitting blue-and-red costume with a cape. Toon calls him Superclone…

The mighty minion casually insults Obelix and learns that he’s not completely invulnerable, but otherwise the visitors are generally benevolent. The paralysis plague is an accidental effect of Toon’s vessel, but a quick adjustment by the strange visitor soon brings the surroundings back to frenetic life.

That’s when the trouble really starts as the villagers – and especially Chief Vitalstatistix – see the giant globe floating overhead as a portent that at long last the sky is falling…

After another good-spirited, strenuously physical debate, things calm down and Toon explains he’s come from the Galactic Council to confiscate an earthly super-weapon and prevent it falling into the hands of belligerent alien conquerors the Nagmas (that’s another anagram) and there’s nothing the baffled Earthlings can do about it…

At the Roman camp of Compendium Centurion Polyanthus is especially baffled and quite angry. His men have already had a painful encounter with the Superclone but the commander refuses to believe their wild stories about floating balls and strangers even weirder than the Gauls, but he’s soon forced to change his mind when a gigantic metal totem pole lands in blaze of flame right in his courtyard.

Out of it flies an incredible, bizarre, insectoid, oriental-seeming warrior demanding the whereabouts of a powerful wonder-weapon. Extremely cowed and slightly charred, Polyanthus tells him about the Magic Potion the Gauls always use to make his life miserable…

The Nagma immediately hurries off and encounters Obelix, but the rotund terrestrial is immune to all the invader’s armaments and martial arts attacks and responds by demonstrating with devastating efficacy how Gauls fight…

After zapping Dogmatix the Nagma retreats and when Obelix dashes back to the village follows him. No sooner has Toon cured the wonder mutt than the colossal Nagma robot-ship arrives, forcing the friendly alien to fly off and intercept it in his golden globe…

The Nagma tries to trade high-tech ordnance for the Gauls’ “secret weapon†but Asterix is having none of it, instead treating the invader to a dose of potion-infused punishment.

Stalemated the Nagma then unleashes an army of automatons dubbed Cyberats and Toon responds by deploying a legion of Superclones. The battle is short and pointless and a truce finds both visitors deciding to share the weapon…

Vitalstatistix is outraged but Getafix is surprisingly sanguine, opting to let both Toon and Nagma sample the heady brew for themselves. The effects are not what the visitors could have hoped for and the enraged alien oriental unleashes more Cyberats in a sneak attack.

Responding quickly, Asterix and Obelix employ two Superclones to fly them up to the marauding robots, dealing with them in time-honoured Gaulish fashion.

The distraction has unfortunately allowed the Nagma to kidnap Getafix and Toon returns to his globe-ship to engage his robotic foe in a deadly game of brinksmanship whilst a Superclone liberates the incensed Druid. None too soon the furious, frustrated Nagma decides enough is enough and blasts off, determined never to come back to this crazy planet…

Down below Polyanthus has meanwhile taken advantage of the chaos and confusion to rally his legions for a surprise attack, arriving just as the Gauls are enjoying a victory feast with their new alien ally. The assault goes extremely badly for the Romans, particularly after a delayed effect of the potion transforms affable Toon into something monstrous and uncanny…

Eventually all ends well and, thanks to technological wizardry, all the earthly participants are returned to their safely uncomplicated lives, once again oblivious to the dangers and wonders of a greater universe…

Fast, funny, stuffed with action and hilarious, tongue-in-cheek hi-jinks, this is a joyous rocket-paced rollercoaster for lovers of laughs and all open-minded devotees of comics. This still-controversial award-winning(Eagle 2006 winner for Best European Comic) yarn only confirmed Uderzo’s reputation as a storyteller willing to take risks and change things up, whilst his stunning ability to pace a tale was never better demonstrated. Asterix and the Falling Sky proves that the potion-powered paragons of Gallic Pride will never lose their potent punch.

© 2005 Les Éditions Albert René, Goscinny-Uderzo. English translation: © 2005 Les Éditions Albert René, Goscinny/Uderzo. All rights reserved.