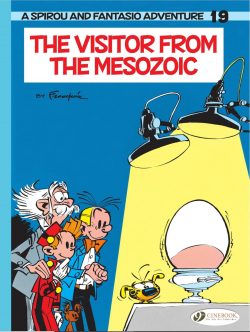

By André Franquin with Greg & Jidéhem, translated by Jerome Saincantin (Cinebook)

ISBN: 978-1-80044-066-1 (Album PB/Digital edition)

Win’s Christmas Gift Recommendation: Marvellous Monster Madness… 9/10

Spirou (whose name translates as “squirrel”, “mischievous” and “lively kid” in the language of Walloons) was created by French cartoonist François Robert Velter – AKA Rob-Vel – for Belgian publisher Éditions Dupuis. He was a measured response to the success of Hergé’s Tintin at rival outfit Casterman. At first, Spirou (with his pet squirrel Spip) was a plucky bellboy/lift operator employed by the Moustique Hotel (an in-joke reference to Dupuis’ premier periodical Le Moustique) whose improbable adventures gradually evolved into astounding and often surreal comedy dramas.

The other red-headed lad debuted on April 21st 1938 in an 8-page, French-language tabloid magazine that bears his name to this day. Fronting a roster of new and licensed foreign strips – Fernand Dineur’s Les Aventures de Tif (latterly Tif et Tondu) and US newspaper imports Red Ryder, Brick Bradford and Superman – Le Journal de Spirou grew exponentially: adding Flemish edition Robbedoes on October 27th 1938, bumping up the page count and adding compelling action, fantasy and comedy features until it was an unassailable, unmissable necessity for Continental kids.

Spirou and chums spearheaded the magazine for most of its life, with many impressive creators building on Velter’s work, beginning with his wife Blanche “Davine” Dumoulin, who took over the strip when her husband enlisted in 1939. She was aided by Belgian artist Luc Lafnet until 1943, when Dupuis purchased the feature, after which comic-strip prodigy Joseph Gillain (“Jijé”) took over.

In 1946, Jijé’s assistant André Franquin inherited the strip. Gradually, he retired traditional short gag-like vignettes in favour of longer adventure serials; introducing a wide and engaging cast of regulars. He ultimately devised a phenomenally popular nigh-magical animal dubbed Marsupilami, who debuted in 1952’s Spirou et les héritiers.

Jean-Claude Fournier succeeded Franquin in 1969 and working for a decade: beginning a succession of reinventions by creator teams that included Raoul Cauvin & Nic Broca; Yves Chaland; and Philippe Vandevelde – writing as “Tome” – & artist Jean-Richard Geurts – AKA Janry.

These last reverently referenced the beloved, revered Franquin era: reviving the feature’s fortunes in 14 albums between 1984-1998. After their departure the strip diversified into parallel strands: Spirou’s Childhood/Little Spirou and guest-creator specials A Spirou Story By… before Lewis Trondheim and the teams of Jean-Davide Morvan/Jose-Luis Munuera and Fabien Vehlmann/Yoann stepped up.

By my count – which includes specials, spin-offs series and one-shots – they cumulatively bring the album count to upwards of 90, but for many of us the Franquin sagas are the epitome and acme of the Spirou experience…

Cinebook have been publishing Spirou & Fantasio’s exploits since October 2009, initially concentrating on translating Tome & Janry’s superb pastiche/homages of Franquin, but for this manic marvel (available in paperback and digitally) they reached back all the way to 1960 for some true Franquin-formulated furore.

Belgian superstar André Franquin was born in Etterbeek on January 3rd 1924. Drawing from an early age, he began formal art training at École Saint-Luc in 1943 but when the war forced the school’s closure a year later, Franquin found animation work at Compagnie Belge d’Animation in Brussels. Here he met Maurice de Bevere (Lucky Luke-creator “Morris”), Pierre Culliford (AKA The Smurfs creator Peyo), and Eddy Paape (Valhardi, Luc Orient).

In 1945 all but Culliford signed on with Dupuis, and Franquin began his career as a jobbing cartoonist/illustrator, crafting covers for Le Moustique and scouting magazine Plein Jeu. Throughout those days, Franquin and Morris were being trained by Jijé – at that time main illustrator at Le Journal de Spirou. He turned the youngsters and fellow neophyte Willy Maltaite – AKA Will (Tif et Tondu, Isabelle, Le jardin des désirs) – into a perfect creative bullpen known as the La bande des quatre or “Gang of Four”. They would revolutionise Belgian comics with their prolific and engaging “Marcinelle school” style of graphic storytelling.

Jijé handed Franquin all responsibilities for the flagship strip part-way through Spirou et la maison préfabriquée, (LJdS #427, June 20th 1946. He ran with it for two decades, enlarging the scope and horizons until it became purely his own. Almost every week fans would meet startling new characters like comrade/rival Fantasio and crackpot inventor the Count of Champignac. Along the way Spirou & Fantasio became globe-trotting journalists, endlessly expanding their weekly exploits in unbroken four-colour glory.

The heroes travelled to exotic places, uncovering crimes, finding the fantastic and clashing with a coterie of exotic arch-enemies like Zorglub and Zantafio, as well as one of the first strong female characters in European comics, rival journalist Seccotine (renamed Cellophine in the current English translation).

In a splendid example of good practise, Franquin mentored his own band of apprentice cartoonists during the 1950s. These included Jean Roba (La Ribambelle, Boule et Bill), Jidéhem (Sophie, Ginger, Starter, Uhu-Man, Gaston Lagaffe) and Greg author of Luc Orient, Bruno Brazil, Bernard Prince, Achille Talon, and Zig et Puce who all worked with him on Spirou et Fantasio.

In 1955, a contractual spat with Dupuis saw Franquin sign with rivals Casterman on Le Journal de Tintin, collaborating with René Goscinny and Peyo whilst creating the raucous gag strip Modeste et Pompon. Within weeks Franquin patched things up with Dupuis and returned to Spirou, subsequently co-creating Gaston Lagaffe (known in Britain as Gomer Goof), but was obliged to carry on his Casterman commitments too…

From 1959, writer Greg and background artist Jidéhem assisted Franquin, but by 1969 the artist had reached his Spirou limit. He quit, taking his mystic yellow monkey with him…

His later creations include fantasy series Isabelle, illustration sequence Monsters and bleak adult conceptual series Idées Noires, but his greatest creation – and one he retained all rights to on his departure – is Marsupilami, which, in addition to comics tales, has become a star of screen, plush toy store, console and albums.

Plagued in later life by bouts of depression, Franquin passed away on January 5th 1997, but his legacy remains: a vast body of work that reshaped the landscape of European comics.

Originally entitled Le voyageur du Mésozoïque and brought to you here as The Visitor from the Mesozoic this album combines a long tail (sorry couldn’t resist!) plus another, shorter adventure by the master crafted in collaboration with co-writer Greg (alias Michel Régnier) and artist Jidéhem – AKA Jean De Mesmaeker. The lead romp comes from 1957 having originated as a serial in Le Journal de Spirou #992-1018 and clearly and cleverly channelling that time’s penchant for rampaging, city-stomping giant monsters…

It begins in the Antarctic as the mushroom-mad Count de Champignac is rescued – much against his will – from his own experiments and frozen doom and brought back to France. He has with him a dinosaur egg that has been frozen for millions of years…

Getting the fragile, precious miracle back to his lab in bucolic Champignac-on-the-Sticks takes all the ingenuity and determination his pals Spirou and Fantasio can muster, but after much fuss and fluster the primordial ovum is stashed in the genius’ workshop and slowly thawing under the gimlet eyes of a handpicked team of fellow mad scientists including Doctors Nero, Schwartz, atomic pariah Sprtschk and Alexandre Specimen – “the Biologist”…

Their bumbling patience is tested to its limits when the mischievous Marsupilami becomes obsessed with the new ball toy and perhaps it’s his terrifying antics that finally force it to hatch…

Everyone is delighted when the mega-million-year-old herbivore pops out, but science is never patient and the bonkers boffins imprudently goose along its development with a little growth formula and aging extracts. Sadly, so does the Marsupilami and when everybody wakes up in the morning they’re greeted by a genial skyscraper saurian with a huge empty belly and a very bad cold…

Soon the big daft brute is shambling through the hamlet looking for browse and causing quite a commotion. The villagers might be used to weird happenings but the government respond with predictable hostility: sending in a tank column and a flight of warplanes…

They prove inefficient and quite ineffective, but the story also generates a wave of controversy. Stridently vocal, violently different pressure groups form: some wanting to save the poor endangered creature and others seeking to preserve the precious landmarks and monuments the beast is trampling. There’s even one guy who wants to make the dinosaur the latest taste sensation in his canned meat factory…

With chaos rampant Spirou looks for a solution to help the creature and finds one, but it depends on manoeuvring the monster to a certain isolated promontory. Thankfully, the Marsupilami has lost patience with his old toy and is ready to step in and step up…

Manic and wildly slapstick in tone and delivery, the story of the big beast is both charming and wickedly satirical and offers a happy ending films like Godzilla, Konga and Gorgo could never have imagined…

The rampaging silliness is counterbalanced by an equally funny but far more sinister pastiche also set in the wild world of the Merlin of Mushrooms. Back-up yarn ‘Fear on the Line’ stems from 1959, serialised as ‘La Peur au bout du fil’ in LJS #1086-1092. Notable for the first crossover appearance of comedy sluggard Gaston Lagaffe, the story details how Champignac distils the chemical essence of evil and accidentally drinks it instead of his coffee. Warned too late, Spirou and Fantasio must chase the now wicked prankster as he wreaks havoc in the village and plants bombs filled with his chemical concoctions. Happily, The Biologist is on hand to offer advice as the clock counts down to doom and our heroes give chase, but in the end it’s the Marsupilami who solves the crisis in his own bombastic manner…

The Visitor from the Mesozoic is the kind of lightly-barbed comedy-thriller that delights readers fed up with a marketplace far too full of adults-only carnage, testosterone-fuelled breast-beating, teen-romance monsters or sickly-sweet fantasy.

Easily accessible to readers of all ages and drawn with all the beguiling style and seductive yet wholesome élan which makes Asterix, Lucky Luke, and Iznogoud so compelling, this is a truly enduring landmark tale from a long line of superb exploits, and deserves to be a household name as much as those series – and even that other kid with the white dog…

Original edition © Dupuis, 1960 by Franquin. All rights reserved. English translation © 2022 Cinebook Ltd.