By Claire Bretécher, translated by Edward Gauvin (Europe Comics)

No ISBNs: digital only

Social satirist and cartoon cultural commentator Claire Bretécher (April 17th 1940 – February 10th 2020), was born in Nantes to a middle class Catholic family. Her heavy-handed father was a jurist whilst mother stayed home to run the house – even as she always encouraged her daughter to be free, autonomous, strong and independent. As a child, Claire read the usual children’s magazines girls were supposed to, but also (boys) comics such as Le Journal de Tintin and Le Journal de Spirou, and drew her own pages until abandoning the “inferior” discipline for abstract art when she began studies at Nantes’ Academy of Fine Arts. On graduation in 1959 she moved to Montmartre, Paris, supplementing with babysitting her main job as a high school drawing teacher, while seeking a proper career in journalism. When her drawings were published in Le Pèlerin, she began contributing to magazines and by the mid-1960s was regularly in publications from Bayard Presse, Larousse and Hatchette. She also worked in advertising as her early comics influences – Will, Hergé and Franquin – expanded to include American “scratchy-line” strip stars Brant Parker (Wizard of Id), Johnny Hart (B.C.), Charles M. Schulz (Peanuts) as well as satirists like James Thurber (The New Yorker, Walter Mitty) and Jules Feiffer (Sick, Sick, Sick, Explainers, Kill My Mother).

Her big bande dessinée break came in 1963 when René Goscinny asked her to illustrate his Le facteur Rhésus for humour magazine L’Os à moelle. Although short-lived, the prestigious partnership brought more work: cartoons, gags, illustration and Claire et Pétronille in Record, pantomimic exploits of adolescent troublemaker Hector in Le Journal de Tintin, Peanuts-derived comedy Les Gnangnan and Les Naufragés (with fellow star-in-waiting Raoul Caunin) at Spirou, and the first of her many medieval satire strips Baratine et Molgaga.

In 1969 at Pilote Bretécher debuted her first great strip character Cellulite (a barbed feminist, “un-beautiful” feudal princess, regarded as the first female antihero in Franco-Belgian comics). After an editorial change, the increasing socially aware-and-active auteur joined fellow creators Nikita Mandryka and Gotlib (Marcel Gottlieb) in quitting to publish their own short-lived but iconic magazine: L’Echo de Savanes which debuted in May 1972. When it folded, Bretécher escaped the comics ghetto and began working in left-leaning mainstream publications with features such as Les Amours Écologiques du Bolot Occidental in ecological monthly Le Sauvage (May 1973) and her second popular masterpiece Les Frustrés which launched in weekly Le Nouvel Observateur as anecdotal cartoon cultural commentary La Page des Frustrés from October 15th of that year. It ran in assorted forms and venues until 1981 by which time she was firmly established as a multi-award-winning author and self-publisher of dozens of books and hundreds of magazine features.

From 1987, she began primarily concentrating on the life of a Gen X French teenager in self-inflicted crisis mode during those difficult years spanning self-declared independence and becoming more or less mature. Simultaneously pompous, angry, spoiled, privileged, resentful, uncertain, intransigent, self-important, trend-seeking, bolshy and determined not to consider the future, Agrippine – or as here Agrippina – roared through dozens of strips that filled 8 albums between 1988 and 2009.

Think of it as a female teen version of Dennis the Menace (UK version) with swearing, scatology, unlovely and messy sex, constant arguments, staggering hilarious rudeness and hysteria and every shocking domestic non-crisis you can imagine… or worse yet remember…

She hates her life and her closest friends, loathes her younger brother and wishes her parents had divorced years ago when she could have got some mileage out of it…

The series always provides sharp and telling observations on generation gaps of every stripe and thus quite naturally made the leap to television for a 26-episode series in 2001.

Most of that unmissable comics cleverness is denied to English-only speakers and readers, but Europe Comics has culled some of the best bits into two albums which any parent would benefit from.

The Trials of Agrippina was first released in 2008 but hasn’t dated at all, serving as a primer with mostly 1-page strips detailing just how bad life can be ‘In the Spotlight’ for ‘Teens’ like ‘Me’, detailing the temptations of ‘Polaroid’ and ‘The Crisis’ of a self-adjudged ‘Success Story’…

Wry and pithy, episodes like ‘Complaints’, ‘Seeing Things’, ‘Blooper’, ‘We Are the Champions’, ‘Candid’ and ‘Myths and Legends’ generally leave our girl ‘Clueless’ and requiring emotional ‘Cleanup’, certain someone has ‘Eyes on You’. The ‘Outpouring’ of misery and bile about the latest ‘Fiasco’ to anyone who will care about being ‘Madly in Love’ is certainly a ‘Challenge’, leaving her ‘Taken for a ride’ at ‘The Beach’, waiting for ‘Miracles’…

Perennial questions confound her generation as they have all others. Quandaries of life like ‘Liver Failure’, ‘Love Letters’, and the eternal ‘Riddle’ of ‘Lurid Nights’, ‘Stars’, ‘The Oath’, being ‘Born Again’, feeling ‘The scream’, ‘The scoop’, or allure or ‘Deadly Arts’ and romantic ‘Strategy’ all show that although she’s always right, Agrippina can never really win…

Even when she finally finds a suitably cool boyfriend – in ghastly pretentious intellectual Morose Mince – it all turns out to be another monumental disappointment and drag from initial ‘Bonding’, through ‘Sweet Nothin’s’, ‘Othello’, with teen ‘High Treason’ hitting ‘The Last Nerve’ as ‘The Specialist’ provokes growing dissatisfaction and musical tastes no longer in ‘Harmony’, and a preference of condoms in ‘Gimmick’ leads to ‘Domestic Strife’, a paucity of ‘Prospects’ and the ‘End of the Line’…

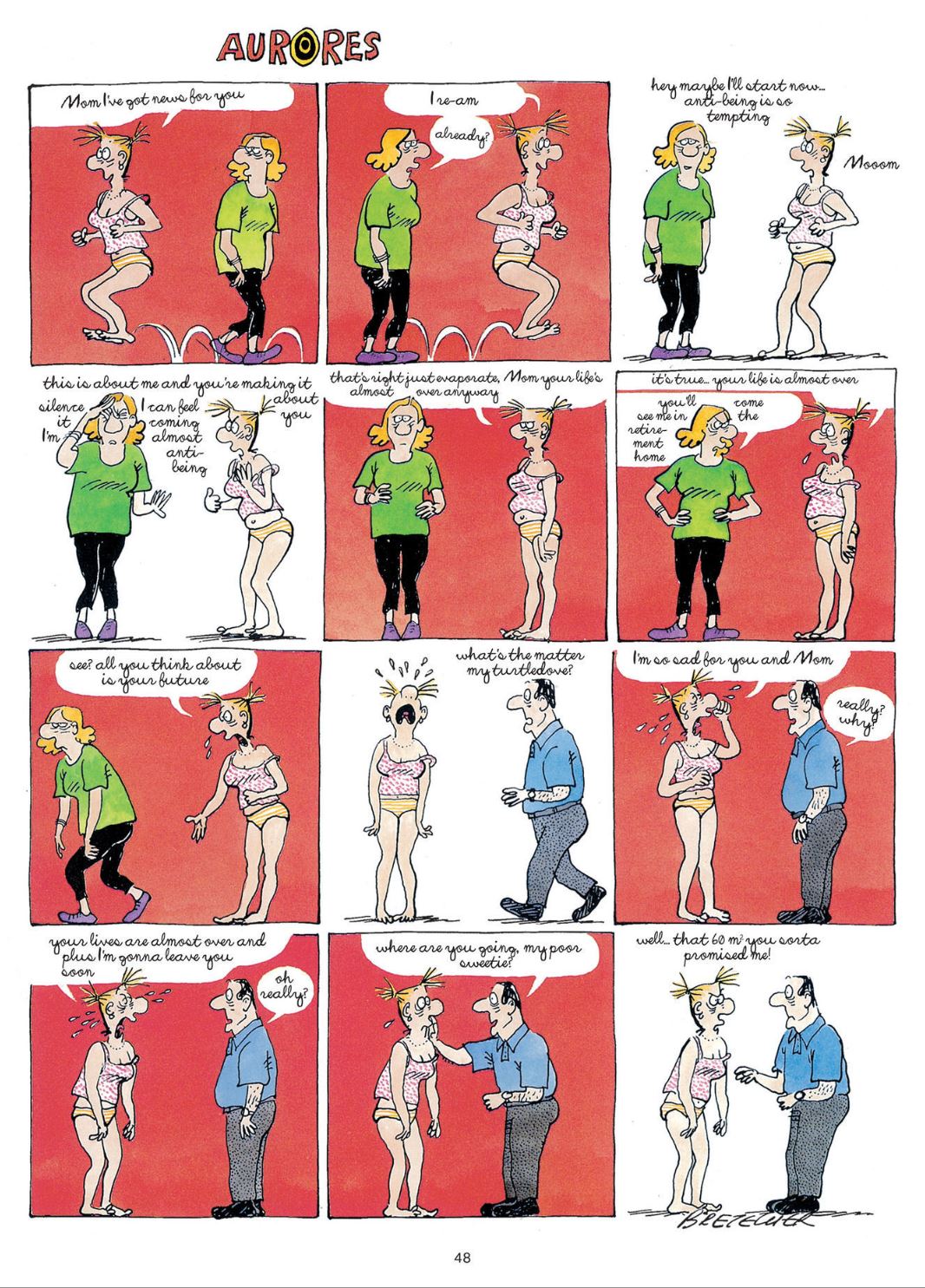

At least mum and dad can now safely offer advice in ‘Aurores’…

Sharp and so very funny – unless you’re a teen reading it – The Trials of Agrippina is a masterpiece of observational comedy no parent can be without.

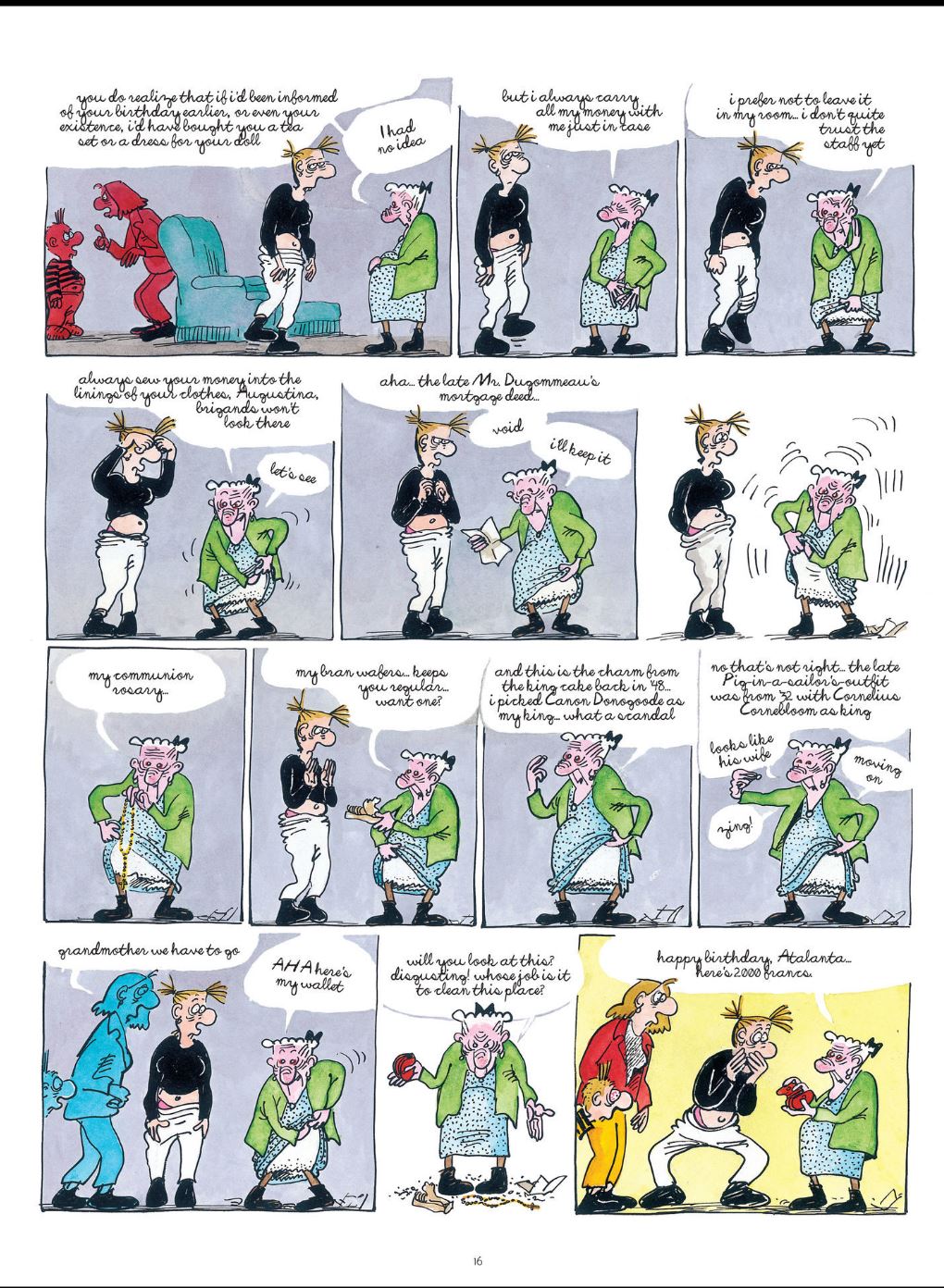

The absolute best seller in the series was fifth album Agrippine et l’Ancêtre first published in 1998 and which we can enjoy as Agrippina and the Ancestor. Here the tale is told in one long epic as our long-suffering lass is dragged into unsuspected maternal dramas when her grandmother – who hasn’t yet coughed up any birthday dough for Agrippina – has an emotional meltdown (and emergency face-lift) after learning her own estranged and despised mother has finally gone into a care home. Now grammy is feeling the weight of years and is after much pressure from daughter and grandchildren – even Agrippina’s vile little brother Byron who also scents guilt money in the air – is convinced to visit Great Grandma Zsa Zsa and reconcile…

Thus opens a manic domestic farce as Commie-hating fireball of prejudice Zsa Zsa runs roughshod over her reunited clan and everyone else in range in an escalating procession of bizarre escapades. These include feeding time at the home, the many downsides of the care professions and the old termagant’s introduction and rapid conquest of computers, virtual reality and robot dogs with her generations of offspring dragged along in her wake. At least studiously sanguine Agrippina gets to meet a kind-of dream lover in the process…

And of course, the teen’s many attempts at explaining the chaos and finding support amongst her own friends are no help at all…

Weird, wild and wonderfully fun, these adventures are pure joy and a lasting tribute to one of the most important women in comics history. Check them out and see for yourself.

© 2015, 2016 – DARGAUD-BENELUX (Dargaud-Lombard s.a.) – Bretécher. All rights reserved.