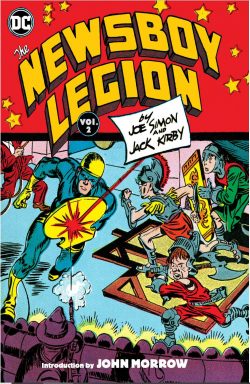

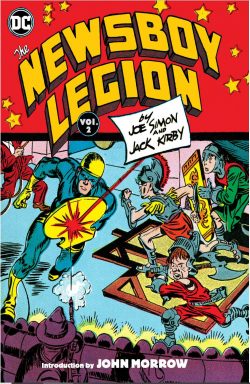

By Joe Simon & Jack Kirby with Don Cameron, Joe Samachson, Ed Herron, Arturo Cazeneuve, Curt Swan, Gil Kane, Joe Kubert & others (DC Comics)

ISBN: 978-1-4012-7236-4 (HB/Digital edition)

Just as the Golden Age of comics was beginning, two young men with big dreams met up and began a decades-long association that was always intensely creative, immensely productive and spectacularly in tune with popular tastes. As kids they had both sold newspapers on street-corners to help their families survive the Great Depression…

Joe Simon was a sharp-minded, talented guy with 5 years’ experience in “real” publishing; working from the bottom up to become art director on a succession of small papers – such as the Rochester Journal American, Syracuse Herald and Syracuse Journal American – before moving to New York City to freelance as an art/photo retoucher and illustrator. Recommended by his boss, Simon joined Lloyd Jacquet’s pioneering Funnies Inc. This was a production “shop”: a conveyor belt of eager talent generating strips and characters for numerous publishing houses eager to cash in on the success of Action Comics and its stellar attraction Superman.

Within days, Simon created The Fiery Mask for Martin Goodman of Timely Comics (now Marvel) and met Jacob Kurtzberg, a cartoonist and animator just hitting his stride with the Blue Beetle for the Fox Feature Syndicate.

Together, Simon and Kurtzberg (who went through many pen-names before settling on Jack Kirby) enjoyed a stunning creative empathy and synergy: galvanizing an already electric neo-industry with a vast catalogue of features and even sub-genres.

They produced influential monthly Blue Bolt, rushed out Captain Marvel Adventures #1 for Fawcett and – after Martin Goodman appointed Simon editor at Timely – created a host of iconic characters such as Red Raven, the first Marvel Boy, Hurricane, The Vision, Young Allies and million-selling mega-hit Captain America.

Famed for his larger-than-life characters and colossal cosmic imaginings, “King” Kirby was an astute, spiritual hard-working family man who lived through poverty, gangsterism and the Depression. He loved his work, hated chicanery of every sort and saw a big future for the comics industry…

When Goodman failed to make good on his financial obligations, Simon & Kirby jumped ship to industry leader National/DC, who welcomed them with open arms and open chequebook. The pair were initially an uneasy fit, bursting with ideas the staid company were not comfortable with and thus given two strips that were in the doldrums until they found their creative feet…

Turning both around Sandman and Manhunter virtually overnight and – once established and left to their own devices – went on to devise the “Kid Gang” genre (technically, it was “recreating” as the notion was one of the duo’s last innovations for Timely as seen in 1941’s Young Allies). The result was unique and trendsetting juvenile Foreign Legion The Boy Commandos.

The little warriors began by sharing the spotlight with Batman in flagship publication Detective Comics, but before long they won their own accompanying solo title – which promptly became one of the company’s top three sellers. Frequently cited as the biggest-selling US comic book in the world at that time – Boy Commandos was such a success that the editors, painfully aware that the Draft was lurking, green-lit the completion of extra material to lay away for when their star creators were called up.

S&K assembled a creative team that generated so many stories in a phenomenally short time that publisher Jack Liebowitz then suggested they retool some of it into adventures of a second kid gang…

Thus was born The Newsboy Legion and super-heroic mentor The Guardian…

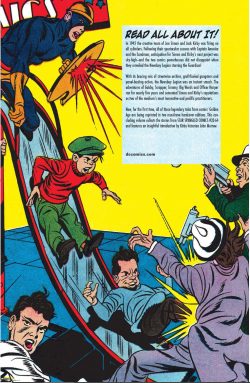

Probably based on the Our Gang/Little Rascals film shorts (1922-1944) and pitched halfway between a surly comedy grotesques and charmingly naive ragamuffins, the Newsboy Legion comprised four ferociously independent orphans living together on the streets of “Suicide Slum” peddling papers to survive. Earnest, good-looking Tommy Tompkins, garrulous genius Big Words, diminutive, hyper-active chatterbox Gabby and feisty, pugnacious Scrapper – whose Brooklyn-based patois and gutsy belligerence usually stole the show – were all headed for a bad end until somebody extraordinary entered their lives…

Their exploits offered a bombastic blend of crime thriller and comedy caper, leavened with dynamic superhero action and usually seen from a kid’s point of view. The series debuted in Star-Spangled Comics #7, forcing Star-Spangled Kid and Stripesy off the covers and to the back of the book. The Legion remained lead feature until the end of 1946 when, without fanfare or warning, issue #65 was published without them.

The lads had been ousted and replaced by solo tales of Robin, the Boy Wonder. His own youth-oriented solo series subsequently ran all the way to SSC #130 in 1952, by which time superhero romps had largely been supplanted throughout the industry by general genre tales.

This second superb collection concludes their Golden Age exploits, with tales from Star-Spangled Comics #33-64 (cover-dated June 1944 – January 1947), including every stunning cover by Kirby, Simon, Fred Ray and teenager Gil Kane all inked by Arturo Cazeneuve, John Daly, Steve Brodie, George Roussos & Stan Kaye. There’s also an informative Introduction from The Jack Kirby Collector/Two Morrows’ publishing guru John Morrow setting the scene for the fun that follows…

In the very first tale, rookie cop Jim Harper adopted a superhero alter ego to administer hands-on justice when The Law was not enough. His vigilantism resulted in the capture of an infamous kidnap ring. Newspapers dubbed the mysterious hero the Guardian of Society and sold like hotcakes on all street corners, making money for even the poorest junior entrepreneurs.

Harper initially had no intention of repeating his foray into vigilantism but when he caught Tommy, Big Words, Gabby and Scrapper shoplifting, his life changed forever. The tough little monkeys were headed for reform school, but he made an earnest plea for clemency on their behalf and the judge appointed him their responsible adult: their “guardian”.

“The Newsboy Legion” were set on a righteous path, but their suspicions were aroused. Frustratingly, no matter how hard they tried, the boys could never prove that their two Guardians were the same guy…

With tales of the war declining in popularity, Star Spangled Comics #33 opens this concluding compilation with ‘The Case of the Bashful Bride!’ Regular illustrator Arturo Cazeneuve limns a fast-paced but uncredited yarn as gangster Sloppy Sam seemingly hangs up his gat after marrying into money. The nosy kids simply can’t accept the transformation and their poking around soon uncovers a cunning plot, cruel criminality and just a hint of hilarious hoity-toity crossdressing behind the scheme…

Naturally, by the time they’re in over their heads, Harper has again swapped his badge and gun for golden helmet and shield to wrap up the case…

The boys’ lives were peppered by dozens of get-rich-quick notions that inevitably uncovered crimes and unleashed chaos. In ‘From Rags to Ruin!’ (#34, by Cazeneuve, July 1944), Gabby discovers the power of positive thinking and talks himself into a high-paying executive position at an insurance company. His dream sours after discovering he’s the figurehead – and fall guy – for a protection racket. Time to call in some old pals…

Still calling himself Eli Katz, future superstar Gil Kane illustrated #35’s ‘The Proud Poppas!’ as the Newsboys adopt a homeless orphan fleeing a cruel and repressive institution. Peter wants to be an artist and gleefully moves into the Boys’ orbit – and shack – but his rightful carers desperately want him back and ruthless kidnappers now know who he is and where he’s hiding…

Cazeneuve returned for ‘The Cowboy of Suicide Slum!’ as grizzled former western sheriff Hawkeye Hawkins of Howlin’ Gulch comes Back East to see the sights. The Legion are all beguiled by his tall tales and before long hip-deep in trouble after they convince the ornery coot to display his talents by going after local gang boss Little Dodo…

After saving a swell from bullies in the slum, Scrapper is offered an apprenticeship by the city’s top gem cutter in ‘Diamonds in the Rough!’ However, as a business prone to criminality, the benefactor expects the fisty firebrand to protect his hands and quit fighting…

When workmen fixing waterpipes trigger a crude oil gusher in Suicide Slum, everybody wants to cash in whilst the toffs in swanky Doughbilt Apartments don’t want their views ruined by derricks. Into that bubbling cauldron of trouble come opportunists; crooks too, so it’s not long until The Guardian and the Legion discover what’s actually going on in ‘Roll Out the Barrels’…

Steve Brodie begins inking Cazeneuve in #39’s ‘Two Guardians Are a Crowd!’ (December 1944) as a crooked doppelganger plays hob with the hero’s reputation and the boys’ conviction of Harper’s double life – until the inevitable face-off – after which notorious thief Danny the Dip bids ‘Farewell to Crime!’ by writing a tell-all memoir. When the kids get involved, it’s exposed as less a confession and more perjury and blame-shifting, leading to the Guardian getting truth – and justice – his way…

When a criminal set fires and create street accidents to tie up first responders in ‘Time Out for the Guardian!’, cop Harper is among the injured. Mistakenly diagnosed with a broken leg, he uses the mistake to convince his wards that the superhero is another guy when they go after the culprits. However, they are just young, not idiots…

In #42, the Legion discovers ‘The Power of the Press!’ when they produce a grassroots periodical going after crooks at ground level. It’s good enough to get them framed by malign mastermind The Undertaker until good old Jim steps in, before the boys test their musical chops in a (naturally fixed and wildly comedic) barbershop quartet singing competition designed to expose the ‘Trials of a Tenor!’

Misguided philanthropy and unthinking privilege steer Ethelreda Winkle and her nephew Cuthbert when the daft dowager sets up an institute to elevate the poor by teaching them proper manners in ‘Etiquette Comes to Suicide Slum!’ With thieves flocking in to improve their chances of better scores, Harper asks the Newsboys to get with the program and learns all is not as seems, after which ‘Crime Gets Clipped!’ finds the lads setting up a …news-gathering “clipping service” and catching a vain bigshot plundering the city’s banks…

‘Clothes Make the Criminal!’ finds the kids on the trail of crooks using a selection of stolen uniforms and costumes to commit outrages before Jim and the boys again prove they have the right stuff…

With George Roussos inking Cazeneuve, ‘The Triumph of Tommy!’ sees the bold Newsboy gunned down by a robber. To recuperate, he’s carted off to Camp Woko-ni-to (“for underprivileged children of the slums”) by his doctor, and when his comrades visit, it sparks another fight when Tommy spots the thug who shot him laying low. Meanwhile, The Guardian has been following another trail and pops up just when he’s most needed…

‘Booty and the Blizzard!’ is one of the few stories we know the writer of. Don Cameron scripts for Cazeneuve & Roussos as an icy cold snap cuts off Suicide Slum and the industrious boys shovel out a network of tunnels for fellow residents trapped behind ten feet of hard-packed snow. Too bad it’s also an ideal escape route for wily bank bandits, until the Guardian learns to ski…

The same creative team measure out ‘One Ounce to Victory!’ as a scrap paper drive gets hyper-competitive when the Newsboys compete with rival news peddlers the Hawker Street Hawks. As if bitter enmity isn’t enough, the effort is made more dangerous after recently released convict Tightlips Leo hides the map to his stashed loot in one of those collected paper piles and resorts to murderous means to retrieve it…

Cover-dated November 1945, Star Spangled #50 features Joe Samachson, Joe Kubert & Roussos adding a flash of film fantasy in ‘The Leopard Man Changes his Spots!’ Here the boys help a meek movie star specialising in monsters channel his inner hero and escape the clutches of a racketeering mobster.

Another industrious enterprise transforms into a means of corralling crooks when the boys start a second-hand apparel business. Naturally, any way to help poor folk advance draws cunning connivers with a perfidious plan, but ‘The Style Show of Suicide Slum’ (Cameron & Kubert) also triggers a wicked comedy of errors when the ugliest jacket on Earth (concealing a fortune in stolen cash) is inadvertently passed from one ungrateful recipient to the next…

Cameron, Cazeneuve & Brodie reunite for #52’s ‘Rehearsal for a Crime!’ as Gabby breaks into an abandoned theatre and mistakes a practise run for robbery for a new play pre-debut. When he comes back with his pals they are all captured and it’s up to Harper to seek them out, shut them down and save the day…

Kirby returned in the next issue where Gabby won a jingle contest – and $500 – and pursued a career in rhyme as ‘The Poet of Suicide Slum!’ (script by Cameron and inked by Brodie). His delusions and propensity for naming gangsters and their plans in his odes soon made him a target for early immortality… until The Guardian applied his own brand of two-fisted criticism…

Another acknowledgement of the rise in western themes informs ‘Dead-Shot Dade’s Revenge!’ (by an uncredited writer, Kirby & Brodie) as a spiky relic of pioneer days drives his “prairie schooner” into Suicide Slum. He’s come 2000 miles in pursuit of Gaspipe Gosser, who stole Dade’s life savings, and it’s all The Guardian can do to stop the old coot shooting him dead like a dawg just to see him drop…

Happily, Gosser’s guilt triggers a pre-emptive strike that gives the hero all he needs to put the thug away, after which Curt Swan & Jack Farr depict how ‘Gabby Strikes a Gusher!’ He had been tending his vegetable garden when he discovered oil, but just as he looks into setting up a company, the thugs who originally stole the stuff came calling…

Cooking for the Newsboys was done on a strict rota basis, with dealer’s choice the prime consideration. When Gabby accidentally came into possession of oysters dropped by fleet-footed Willy Wetsell, he thought it solved his problem of what the gang would eat that night.

Instead, each mollusc contained a superb, huge fully processed Arabian pearl and Jim Harper realised that this ‘Treasure of Araby’ (art by Kirby & Ray Burnley) was far more than chance and not in the least lucky…

Kirby & John Daly limned Star Spangled Comics #57’s cunning shocker as mobster Snake Huggins resolved to fix the interfering brats for good. His plan was to hit him at his weakest point and resulted in ‘A Recruit for the Legion!’ but wealthy Timothy Tuck was not what he seemed and proved a far bigger threat that he looked…

Kirby handled exotic diversion ‘Matadors of Suicide Slum!’ as the boys befriend elderly janitor Perez and hear rousing tales of his glory days in the bullrings of Mexico. Coincidentally, Yankee businessmen are trying to bring the bloody sport to Suicide Slum, leading to a decades-delayed concluding duel between the man and his nemesis El Diabolo. Only, it’s not quite as they recalled or any onlooker quite expected…

From sentimental slapstick, we turn to criminal mystery in Kirby’s Daly inked ‘Answers, Inc.!’ (#59, August 1946) wherein Tommy cashes in on an unsuspected gift for solving riddles, puzzles and general knowledge quizzes. Although he’s smart, he’s still a kid though and when a cunning cove poses a pithy conundrum, Tommy hands over a method for a foolproof heist. Happily, jaded, cynical Jim Harper is on hand to ask his own difficult questions whilst The Guardian is ready to answer them…

Ed Herron, Swan and Stan Kaye then detail a whimsical winner as Scrapper seeks to become ‘Steve Brodie Da Second!’ to one-up friendly rivals the Boy Commandos. The Brodie in question is not the inker, but the turn of the century sportsman who claimed to have survived jumping off the East River Bridge. Here, however, Scrapper’s idiotic emulation ends when he jumps right into a gangster’s secret submarine, and silly season stunt escalates to front page crime caper…

Swan & Kaye then continued the new trend for stunts as Guardian’s pursuit of a crook leads to a syndicate dictating the demise of him and the Newsboy Legion under the pretence of sponsoring them in ‘The Great Balloon Race!’ across America, after which ‘Prevue of Tomorrow’ sees a mysterious stranger spark chaos by handing out papers offering news from 24 hours into the future. Of course for our heroes forewarned is simply forearmed…

Brodie inked Swan on penultimate outing ‘Code of the Newsstand!’ as the boys visit Chinatown just as Harper enters the enclave to find escaped convict Stiletto Mike. Of course, they are first to find the felon but it’s The Guardian who has the last word… and punch.

Cover-dated January 1947, Star Spangled Comics #64 closed the Newsboy Legion’s eclectic run with ‘Criminal Cruise!’ wherein Swan & Brodie had the kids literally sailing off into the sunset after winning an all-inclusive holiday to the South Seas. Naturally, trouble followed with lost tickets, stowaways and a gang of jewel thieves spicing up the voyage…

And that was that for almost 25 years, until Kirby brought them back in Superman’s Pal Jimmy Olsen #133 (October 1970), spearheading his mega revitalisation of DC’s continuity – but let’s talk of that another day…

There is a glorious abundance of Jack Kirby material available these days: true testament to his influence and legacy, with this magnificent and compelling collection in collaborations with fellow pioneer Joe Simon being another gigantic box of delights perfectly illustrating the depth, scope and sheer thundering joy of the early days of comics. Funny, thrilling and ideally accessing simpler days, this is a treat every fan should enjoy and share.

© 1944, 1945, 1946, 2017 DC Comics. All rights reserved.