By Andre Franquin, translated by Jenna Allen (Fantagraphics Books)

ISBN: 978-1-68396-091-1 (HB)

Like so much in Franco-Belgian comics, it all starts with Le Journal de Spirou. The magazine was first seen on April 2nd1938, with its engaging and eponymous lead strip created by Rob-Vel (François Robert Velter). In 1943 publishing giant Dupuis purchased all rights to the comic and its titular star, after which comic-strip prodigy Joseph Gillain (“Jijéâ€) took the helm.

In 1946 Jijé’s assistant assumed the creative reins, gradually side-lining the previously-established short gag vignettes in favour of extended adventure serials. He introduced a broad, engaging cast of regulars: adding to the mix phenomenally popular rare beast and animal marvel Marsupilami (first seen in Spirou et les héritiers in 1952 and eventually a spin-off star of screen, plush toy store, console games and albums in his own right).

He continued crafting increasingly fantastic tales and absorbing Spirou sagas until his resignation in 1969. Throughout that period the creator was deeply involved in the production of the weekly Spirou comic and increasingly beset by depression and other mental health issues.

André Franquin was born in Etterbeek, Belgium on January 3rd 1924. Drawing from an early age, the lad only began formal art training at École Saint-Luc in 1943. When the war forced the school’s closure a year later, he found work at Compagnie Belge d’Animation in Brussels where he met Maurice de Bévère (AKA Lucky Luke creator “Morrisâ€), Pierre Culliford (Peyo, creator of The Smurfs and Benny Breakiron) and Eddy Paape (Valhardi, Luc Orient).

In 1945 all but Peyo signed on with Dupuis, and Franquin began his career as a jobbing cartoonist/illustrator, producing covers for Le Moustique and scouting magazine Plein Jeu. During those early days, Franquin and Morris were being tutored by Jijé, who was the main illustrator at Le Journal de Spirou. He turned the youngsters – and fellow neophyte Willy Maltaite (AKA “Will†– Tif et Tondu, Isabelle, Le jardin des désirs) – into a smoothly functioning creative bullpen known as La bande des quatre or “Gang of Fourâ€. They later reshaped and revolutionised Belgian comics with their prolific and engaging “Marcinelle school†style of graphic storytelling…

Jijé handed Franquin all responsibilities for the flagship strip part-way through Spirou et la maison préfabriquée (Spirou #427, June 20th 1946). The new kid ran with it for the next two decades; enlarging the scope and horizons of the feature until it became purely his own. Almost every week fans would meet startling new characters such as comrade/rival Fantasio or crackpot inventor and Merlin of mushroom mechanics the Count of Champignac.

Spirou & Fantasio became globe-trotting journalists, travelling to exotic places, uncovering crimes, exploring the fantastic and clashing with a coterie of exotic arch-enemies. However, throughout all that time Fantasio was still a full-fledged reporter for Le Journal de Spirou and had to pop into the office all the time.

While there he conceived another landmark icon, a comedic foil and meta-real alter ego who was an accident-prone, big-headed junior in charge of minor jobs and dogs-bodying. His name was Gaston Lagaffe and through him Franquin expressed his unruly dissident opinions and tendencies…

Gaston – who debuted in #985, (February 28th 1957) – grew to be one of the most popular and perennial components of the comic. In terms of entertainment schtick and delivery, older readers will certainly recognise beats of Jacques Tati and timeless elements of well-meaning self-delusion British readers will recognise from Some Mothers Do Have ‘Em or Mr Bean. It’s slapstick, paralysing puns, pomposity lampooned and no good deed going noticed, rewarded or unpunished…

In a splendid example of good practise, Franquin mentored his own band of apprentice cartoonists during the 1950s. These included Jean Roba (La Ribambelle, Boule et Bill/Billy and Buddy); Jidéhem (Sophie, Starter, Gaston Lagaffe) and Greg (Comanche, Bruno Brazil, Bernard Prince, Zig et Puce, Achille Talon), who all worked with him on Spirou et Fantasio. In 1955, a contractual spat with Dupuis saw Franquin briefly enlist with rivals Casterman on Le Journal deTintin, where he collaborated with René Goscinny and old pal Peyo whilst creating the fashion/lifestyle domestic comedy gag strip Modeste et Pompon. Franquin almost immediately  patched things up with Dupuis and returned to Spirou, subsequently co-creating Gaston Lagaffe (known in Britain these days as Gomer Goof) in 1957, but was obliged to carry on his Casterman commitments too…

From 1959, writer Greg and background artist Jidéhem assisted Franquin, but by 1969 the artist had reached his Spirou limit. He quit, taking his mystic yellow monkey with him…

Later creations include fantasy series Isabelle, illustration sequence Monsters and this arcane convergence of bleak gallows humour, adult conceptual nihilism and impassioned social and ideological frustration lensed through comedy. If you’re aware of the later work of Spike Milligan, you’ll know instinctively what I mean. The strip and original series title Idées Noires has entered into common usage in French-speaking countries, as a term for gloomy or negative thoughts: dark ideas daily obsessing people in crisis expunged and expressed through strident manic humour…

It began as he recuperated from a heart attack in 1975. Id̩es Noires was part of an insert comic РLe Trombone illustr̩ Рhe and Yvan Delporte produced for weekly Le Journal de Spirou beginning with the March 17th 1977 issue. After 30 mini-issues, and with the global situation looking increasingly fraught, a revitalised Franquin took the strip to mature reader magazine Fluide Glacial where it ran until 1983.

Plagued throughout his life by depression, Franquin passed away on January 5th 1997, but his legacy remains: a vast body of work that reshaped the landscape of European comics.

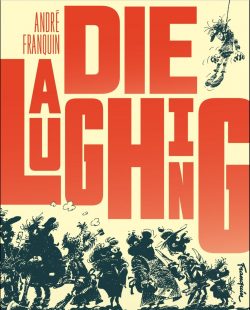

In 2018, Fantagraphics gathered and translated the strips, releasing them as Die Laughing.

As seen in Cynthia Rose’s erudite and informative Introduction – ‘Liberty, Audacity, Hilarity: André Franquin‘ – the peripatetic feature gave Franquin room to address his allegiances with issues of environmentalism, animal cruelty, political duplicity and plain old human insanity and strike back with the best weapons in his arsenal: sarcasm, mockery and despairing outrage.

To further demarcate the series from past works, the images are delivered in scratchy, shocking lines and solid blacks, with elements reversed out: it’s a world of silhouettes, deep shadows and brooding forward spaces and middle-grounds, with no extraneous detail: all delivered in eerie evocative, expressionist monochrome, rather than the shining and substantial Disney-inspired colour of Spirou and the Marsupilami…

This hardback and digital compilation consists of half and full page shorts plus a few longer cartoon strips lampooning and spearing, smug pomposity, business greed, military-industrial chicanery and ruthlessness, planetary abuse such as inflicted by oil companies and the global arms race. There are many mordant observations on sport, war for profit, the death penalty (still the guillotine, for Pete’s sake!), alien abduction, the rat race, sheer random surreal absurdism, all skewered by a sense of cosmic justice acknowledged, if not satisfied…

A constant theme returned to with merciless regularity is bloodsports and the kind of arsehole who finds fun and feels magnified by pointless slaughter. Especially singled out are those French “traditionalists†who simply must slaughter songbirds in their thousands every year as they migrate to and from Europe…

Franquin was a master of comedy in all its aspects from whimsically light to trenchantly black-edged. Come see how and why…

Die Laughing © 2018 by Fantagraphics Books, Inc. Comics © Editions Audie/Franquin Estate. All rights reserved. Introduction © 2018 by Cynthis Rose. Afterword © 2018 Gotlib Estate. All other images and text © 2018 their respective copyright holders. All rights reserved.