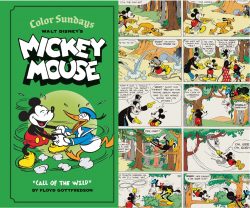

By Floyd Gottfredson & various: edited by David Gerstein & Gary Groth (Fantagraphics Books)

ISBN: 978-1-60699-643-0 (HB/Digital edition)

Win’s Christmas Gift Recommendation: A Mouse in Every House… 10/10

Happy technical 100th Anniversary Disney, but we all know it all REALLY started with this little guy…

As collaboratively co-created by Walt Disney & Ub Iwerks, Mickey Mouse was first seen – if not heard – in silent cartoon Plane Crazy. The animated short fared poorly in a May 1928 test screening and was promptly shelved. That’s why most people who care cite Steamboat Willie – the fourth Mickey feature to be completed – as the debut of the mascot mouse and co-star and paramour Minnie Mouse, since it was the first to be nationally distributed, as well as the first animated feature with synchronised sound. The astounding success of the short led to a subsequent and rapid release of fully completed predecessors Plane Crazy, The Gallopin’ Gaucho and The Barn Dance, once they too had been given soundtracks. From those timid beginnings grew an immense fantasy empire, but film was not the only way Disney conquered hearts and minds. With Mickey a certified solid gold sensation, the mighty mouse was considered a hot property and soon joined America’s most powerful and pervasive entertainment medium: comic strips…

Floyd Gottfredson was a cartooning pathfinder who started out as just another warm body in the Disney Studio animation factory. Happily, he slipped sideways into graphic narrative and evolved into a pioneer of pictorial narratives as influential as George Herriman, Winsor McCay and Elzie Segar. Gottfredson’s Mickey Mouse entertained millions – if not billions – of eagerly enthralled readers and shaped the very way comics worked. Via some of the earliest adventure continuities in comics history he took a wildly anarchic animated rodent from slap-stick beginnings and transformed a feisty everyman/mouse underdog into a crimebuster, detective, explorer, lover, aviator and cowboy. Mickey was the quintessential two-fisted hero whenever necessity demanded. In later years, as tastes – and syndicate policy – changed, Gottfredson steered that self-same wandering warrior into a sedate, gently suburbanised lifestyle, employing crafty and clever sitcom gags suited to a newly middle-class America: comprising a 50-year career generating some of the most engrossing continuities the comics industry has ever enjoyed.

Arthur Floyd Gottfredson was born in 1905 in Kaysville, Utah, one of eight siblings in a Mormon family of Danish extraction. Injured in a youthful hunting accident, Floyd whiled away a long recuperation drawing and studying cartoon correspondence courses. By the 1920s he had turned professional, selling cartoons and commercial art to local trade magazines and Big City newspaper the Salt Lake City Telegram.

In 1928, he and wife Mattie moved to California where, after a shaky start, the doodler found work in April 1929 as an in-betweener with the burgeoning Walt Disney Studios. Just as the Great Depression hit, he was personally asked by Walt to take over the newborn but already ailing Mickey Mouse newspaper strip. Gottfredson would plot, draw and frequently script the strip for the next five decades: an incredible accomplishment by of one of comics’ most gifted exponents.

Veteran animator Ub Iwerks had initiated the print feature with Disney himself contributing, before artist Win Smith was brought in. The nascent strip was plagued with problems and Gottfredson was only supposed to pitch in until a qualified regular creator could be found.

His first effort saw print on May 5th 1930 (his 25th birthday) and Floyd just kept going for fifty years. On January 17th 1932, Gottfredson crafted the first colour Sunday page, which he also handled until retirement. At first he did everything, but in 1934 Gottfredson relinquished scripting, preferring plotting and illustrating the adventures to playing about with dialogue. Thereafter, collaborating wordsmiths included Ted Osborne, Merrill De Maris, Dick Shaw, Bill Walsh, Roy Williams & Del Connell. At the start and in the manner of film studio systems, Floyd briefly used inkers such as Ted Thwaites, Earl Duvall & Al Taliaferro, but by 1943 had taken on full art chores.

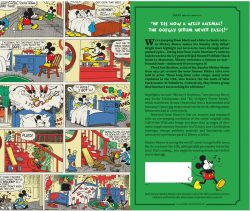

This superb archival compendium – part of a magnificently ambitious series collecting the creator’s entire canon – re-presents the initial colour sequences, jam-packed with thrills, spills and chills, whacky races, fantastic fights and a glorious superabundance of rapid-fire sight-gags and verbal by-play. The manner by which Mickey became a syndicated star is covered in various articles at the front and back of this sturdy tome devised and edited by truly dedicated, clearly devoted fan David Gerstein who also provides an Introduction. The tome is stuffed with lost treats such as a try-out sketch (of the Wolf Barker storyline) by Carl Barks from 1935 when he joined Disney Studios.

Under the guise of Setting the Stage unbridled fun and incisive revelations begin with J.B. Kaufman’s ‘Mickey’s Sunday Best: A New Arena’ introducing us to this unique graphic world before Kevin Huizenga’s Appreciation ‘A Brief Essay About Floyd Gottfredson’ details the pictorial pathfinder’s visual innovations prior to The Sundays: Floyd Gottfredson’s Mickey Mouse Stories With Introductory Notes concluding scene-setting with Gerstein offering some preliminary insights in ‘Sunday Storytelling’…

At the start – just like the daily feature – the strip was treated like an animated feature, with diverse hands working under a “director” and each day seen as a full gag with set-up, delivery and a punchline, usually all in service to an umbrella story or theme. Such was the format Gottfredson inherited from Walt Disney for his first full yarn, and here generally unconnected Gag Strips spanning January 10th to July 24th 1932 were by Duval (story & pencils) and Gottfredson until they switched and Floyd drew with Duval and Al Taliaferro inking. The result was a barrage of fast-paced and funny anthropomorphic animal antics starring Mickey, Minnie Mouse, Horace Horsecollar, Clarabelle Cow, plus prototype pet Pluto dodging dogcatchers, visiting circuses and funfairs, fighting fires, skating, fighting Indians (sorry, it was an inescapable factor of less-evolved times), joyriding, farming, fishing, gardening, cooking, quarrelling, messing with model planes and trying to make money. As the weekly funfest progressed, Pluto’s part grew exponentially and – after a monochrome poser for film short Puppy Love (1933) – a brief briefing in ‘The Peter Principle’ leads to the first extended storyline.

Running from July 31st to September 4th 1932 ‘Dan the Dogcatcher’ saw Gottfredson inked by Ted Thwaites in a dogged (sorry, not sorry) battle of wills as future returning foe Peg-Leg Pete debuted as an unscrupulously uncivil civil servant seeking to put Pluto in the pound at any cost. The tale wandered eccentrically and frenetically all over the small town scenario, adding drama and bathos to chaos and comedy before seamlessly slipping into more Gag Strips (January 10-July 24 1932) with story & pencils by Duval & Gottfredson and inks by Duval and Al Taliaferro.

One last Gag Strip (September 11th 1932 by Gottfredson & Thwaites neatly segues into ‘Mickey’s Nephews’ (September 18th – November 6th 1932 by Gottfredson & Thwaites) and is notable for introducing Mickey’s mischief-making nephews when he looks after the anarchic offspring of neighbour Mrs. Fieldmouse for a few weeks. The sentient cyclones soon start calling the guardian/jailer “unca Mickey”…

Gag Strips spanning November 13th 1932 to January 22nd 1933 (story Gottfredson & Webb Smith, pencils by Gottfredson inked by Thwaites & Taliaferro) leads to an essay detailing ‘Mickey’s Delayed Drama’ before landmark romp ‘Lair of Wolf Barker’ (January 29th – June 18th) changed the tone of the strip forever.

The first extended Mickey Sunday colour epic was partially scripted by Osborne and inked by Taliaferro & Thwaites, but is pure Gottfredson at his most engaging: a rip-roaring comedy western featuring a full wide-screen repertory cast: Mickey, Minnie, Horace, Clarabelle and Goofy, who originally answered to the moniker Dippy Dog.

The gang head west to look after Uncle Mortimer’s sprawling ranch and enjoy fresh air and free lodgings but after meeting his foreman Don Poocho stumble into a baffling crisis. Mortimer’s cattle are progressively vanishing, with the unsavoury eponymous villain riding roughshod over the territory and terrorising assorted characters and stock figures culled from a million movies. Desperados and deviltry notwithstanding, before long Barker gets his ultimate and well-deserved come-uppance thanks the Mouses’ valiant efforts. This is action comics on the fly, with plenty of rough-&- tumble action, twists, turns and surprises always alloyed to snappy, fast-packed sight and slapstick gags.

Without pausing for breath the cast’s return home leads to more unconnected frenzied Gag Strips (June 25th 1933 to March 4th 1934: story by Osborne, pencils by Gottfredson and inks by Thwaites & Taliaferro) with Mickey as much silly nuisance as closet hero until extended tales return, with ‘The Longest Short Story Ever Told!’ first supplying some context about the filmic origins of the next epic ‘Rumplewatt The Giant.’

The fantasy fable ran March 11th to April 29th 1934 by Osborne, Gottfredson, Thwaites & Taliaferro and sees Mickey reading a bedtime story to youngsters with himself as a giant killer in fairyland, after which rustic domesticity and free enterprise dominate as Mickey and Minnie anticipate – over a number of episodes – replacing the decrepit horse in his new delivery service. Many mishaps occur until ‘Tanglefoot Pulls His Weight’ (May 6th – June 3rd), and a single Gag Strip (June 10th 1934) leads to essay ‘Call of the Wild’ debating the history and tangled relationship of Horace Horsecollar, Clarabelle and Goofy prior to Osborne, Gottfredson & Taliaferro dipping into sinister mad science courtesy of ‘Dr. Oofgay’s Secret Serum’ (June 17th– September 9th 1934). A double date camping trip to the woods goes awry when the reclusive scientist – seeking a way to tame ferocious animals by chemistry, instead injects Horace with the antidote turning him into a rampaging beast…

‘TOPPER Strip “Introducing Mickey Mouse Movies”’ (June 24 1934 by Osborne, Gottfredson, & Taliaferro) reveals the ancillary feature that augmented the weekly feature and precedes more unconnected but house-based Gag Strips (September 16th to December 2nd 1934) and article ‘Death Knocks, Fate Pesters’ explores the strip’s early use of what we now call disaster capitalism before ‘Foray to Mt. Fishflake’ (December 9th 1934 to February 10th 1935 by Osborne, Gottfredson & Thwaites) finds the four friends seeking to scale a peak for prize money – a thrilling romp that led to also included Gag Strips from January 27th to February 10th and saw the comics debut of new Disney screen sensation Donald Duck…

‘Beneath the Overcoat’ is a treatise on Osborne, Gottfredson & Thwaites’ landmark crime yarn running from February 17th to March 24th that reshaped the Mouse’s modus operandi and future exploits before serialised gem ‘The Case of the Vanishing Coats’ sees Mickey helping Donald’s Uncle Amos solve a baffling mystery of invisible shoplifters just before Morty and Ferdie Fieldmouse return to Gag Strips appearing between March 31st and July 21st in pranks and hijinks exacerbated by wild spark Donald….

Another Gottfredson promo drawing precedes the next big addition with text tract ‘Hoppy the Ambassador’ bringing readers up to speed on previous antipodean animals just so Osborne, Gottfredson & Thwaites can fully enthral and beguile with the saga of originally unwelcome new pet ‘Hoppy the Kangaroo’ (July 28th – November 24th). The bouncy ’roo eventually wins everyone over after a boxing bout with a gorilla named Growlio, managed by old enemy Peg-Leg Pete…

Osborne, Gottfredson & Thwaites’ Gag Strips carry the feature over the Holiday period of December 1st – 29th 1935, but although the chronological cartooning officially concludes here, there’s still a wealth of glorious treats and fascinating revelations in store. A 1935 painted colour cover by Gottfredson & Tom Wood for Italian magazine Modellina takes us into The Gottfredson Archives: Essays and Special Features section that follows. Here a picture packed essay on ‘The Monthly “Sundays”’ by Gerstein & Jim Korkis reveals a long-lost publication for Masonic youth in “Mickey Mouse Chapter” (A Mickey Supplement) sourced fromInternational DeMolay CordonVol. 1 #9-11, Vol. 2 #1-2 (December 1932 – May 1933) and written by Fred Spencer (first 4 strips) & Gottfredson (5), with art by Spencer.

International reprints of our opening saga are seen in ‘Gallery Feature – Gottfredson’s World: Dan the Dogcatcher’ whilst background and context on ‘The Cast: Morty and Ferdie’ by Gerstein segues into a sidebar project detailed in ‘Behind the Scenes: Minnie’s Yoo-Hoo’.

More international editions can be seen in ‘Gallery Feature – Gottfredson’s World: Mickey’s Nephews.’ A foray into pop-up books is covered in Gerstein’s ‘The Comics Department at Work: The Mouseton Pops’, supplemented with covers and interior art from Gottfredson, Taliaferro & Tom Wood. More reprint covers of many nations are gathered in ‘Gallery Feature – Gottfredson’s World: Early Epics’ after which ‘The Gottfredson Gang: In “Their Own” Words’ sees Gerstein revisit text by Irene Cavanaugh from 1932, introducing Dippy Dawg to the world and revealing Mickey’s astrological aspects…

Topolino covers fill the ‘Gallery Feature – Gottfredson’s World: Going Places’ whilst storyboards by Homer Brightman adorn Gerstein’s ‘Behind the Scenes: Interior Decorators’ before William Van Horn’s ‘“Wrapping Up” The Case of the Vanishing Coats’ focuses on later reprintings and alterations…

Another tranche of foreign imports can be seen in ‘Gallery Feature – Gottfredson’s World: Curiosities of 1935’ and ‘Gallery Feature – Gottfredson’s World: Hoppy the Kangaroo’ in advance of feature article ‘The Heirs of Gottfredson’s World: Topolino’ by Sergio Lama & Gerstein leading to capacious translated Christmas-themed Gag Strips in Verse (A Mickey Supplement) offering excerpts from Italian Il Popolo Di Roma (May-July 29 1931: story by Guglielmo Guastaveglia); The Delineator (December1932: story & art by Gottfredson et al) and Italian Topolino #1 & 7 (December 31st 1932 & February 11th 1933 with story & art by Giove Toppi & Angelo Burattini) before closing with an illustrated quote – “Any time you can tell a story…” – giving Gottfredson himself the last word…

Floyd Gottfredson’s influence on not just Disney’s canon but sequential graphic narrative itself is inestimable: he was among the first to produce long continuities and “straight” adventures, pioneered team-ups and invented some of the art form’s first “super-villains”.

When Disney killed their continuities in 1955, dictating henceforth strips would only contain one-off gag strips, Floyd adapted seamlessly, working until retirement in 1975. His last daily appeared on November 15th with a final Sunday published on September 19th 1976.

Like all Disney creators, Gottfredson worked in utter anonymity. However, in the 1960s his identity was revealed and the roaring appreciation of previously unsuspected hordes of devotees led to interviews, overviews and public appearances, leading to subsequent reprinting in books, comics and albums which now all carried a credit for the quiet, reserved master. Floyd Gottfredson died in July 1986. Thankfully we have these Archives to enjoy, inspiring us and hopefully a whole new generation of inveterate tale-tellers…

Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse Color Sundays “Call of the Wild” © 2013 Disney Enterprises, Inc. Text of “Mickey’s Sunday Best: A New Arena” by J.B. Kaufman is © 2013 by J.B. Kaufman. All contents © 2013 Disney Enterprises unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.